House of Hackney has come together with The Library of Esoterica to bring you a season of Plant Magick through spellbinding essays, events, art and interiors, with the plant as muse.

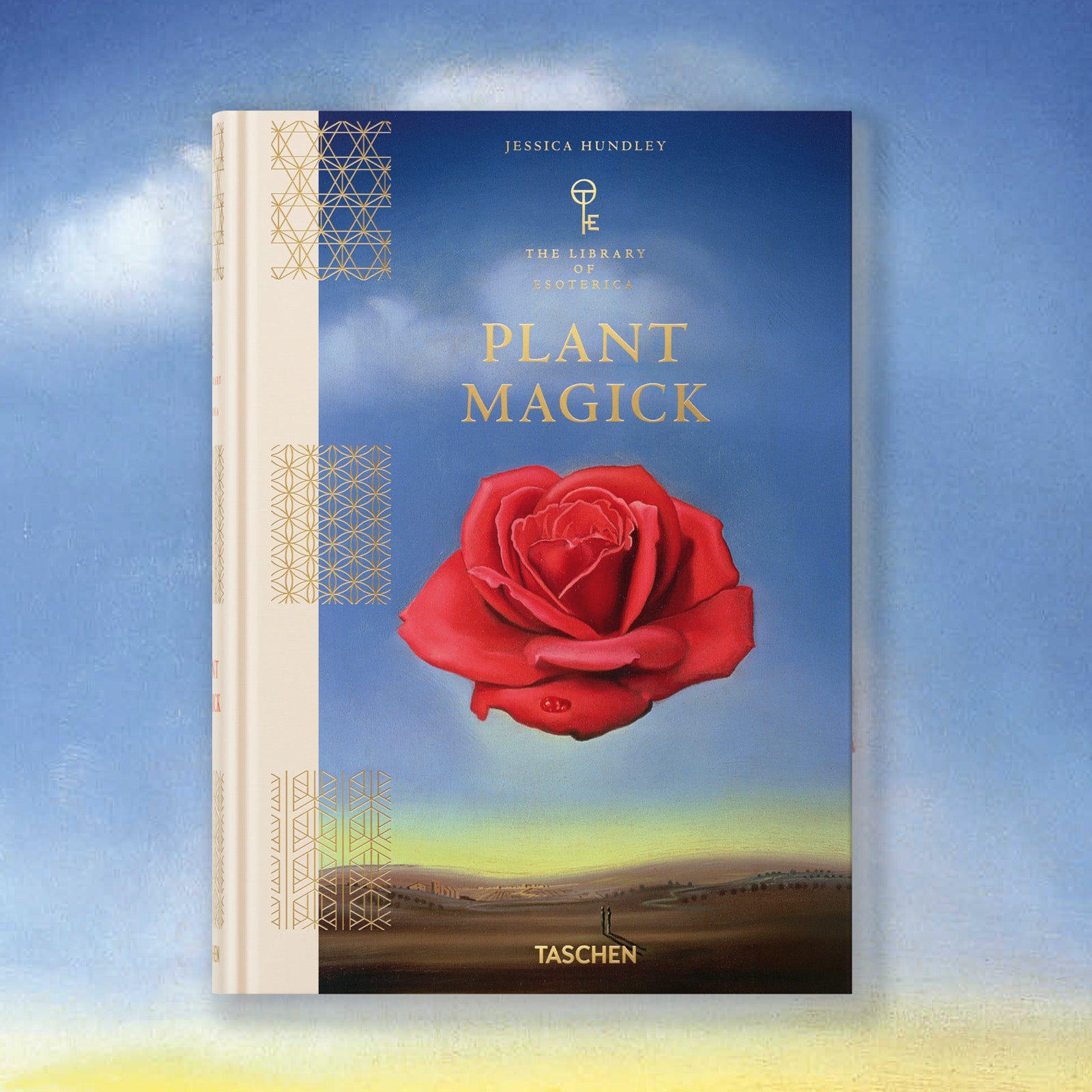

From root to vibrant blossom, Taschen’s Plant Magick explores the fertile, interconnected history between plants and people. This creative partnership is rooted in a shared reverence for the enchanted, the unseen, and the profound beauty that surrounds us.

Nature itself is the best physician.

– Hippocrates of Kos, Greek physician thought to have been born in 460 BCE and considered the forefather of modern medicine

-

The use of plants in healing is a practice that goes back as far as ancient Sumer. Archeologists have discovered written documentation of medicinal botanicals, carved by Sumerians onto clay tablets dating to approximately 3000 BCE. Employing the curative qualities of plants, flowers, herbs, and certain species of mushrooms, may go back even farther still, to the very dawn of human- kind, to our ancestors, plucking Nettle and Dandelions to fight off illness, or tending a wound with an herbal poultice in the flickering firelight of a cave dwelling. The Ebers Papyrus, an early Egyptian scroll thought to be written in 1550 BCE, documents hundreds of plants, and their medical applications. In Hindu Vedic scriptures, the use of plant medicine is mentioned in various writings, most notably in the Atharva Veda, a volume likely penned sometime between 1200 and 1000 BCE. In China, the famous texts of the Shennong Ben Cao Jing, writ- ten between 206 BCE and 220 CE were said to document the use of hundreds of healing botanicals. Ancient Greek physicians, includ- ing those schooled under Hippocrates, born in 460 BCE and widely considered to be “The Father of Medicine,” often prescribed herbal remedies native to the Mediterranean, from Rue to Sage, Oregano to Bay Laurel. There are hundreds of plant-based prescriptions included in The Hippocratic Corpus, the collection of writings most associated with Hippocrates and his teachings. In 60 CE the Greek scholar and physician Pedanius Dioscorides wrote one of the most extensive overviews of plant medicine ever recorded, De materia medica, a work which would serve as a foundational manual for much of the world, for the next thousand years and more.

The gifted Persian philosopher Ibn Sina created two important volumes of plant medicine with his Canon of Medicine, published in 1025 and The Book of Healing, published in 1027. In Baghdad of the 11th century, the Islamic physician Ibn But·laˉn compiled the vast encyclopedia known as Historia Plantarum. The latter used the work of Dioscorides as a primary source, with But·laˉn expanding upon the Greek author’s work with information on additional plants, herbs, and botanicals native to the Middle East and Asia. This was just one of the many books that used Dioscorides’ famous volume as inspiration. De materia medica has become, over the course of two centuries, perhaps the most influential tomes on plant medicines ever written. Translated into Arabic, Greek, and Latin, and illustrated with detailed drawings, copies of De materia medica were painstakingly hand-made into the Middle Ages. With the advent of the printing press the book was mass distributed in multiple languages and finally translated into English in 1655 by the botanist John Goodyer. Goodyer, along with fellow botanist Thomas Johnson, was also responsible for editing and updating the herbalist John Gerard’s Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes – a thousand page illustrated overview of herbs and plants, first published in 1597. Gerard’s original manuscript took much of its information from Cruydeboeck (herb book) written by the Dutch physician and botanist Rembert Dodoens in 1554.

These books, as well as the Renaissance-era innovations of woodblock printing and engraving, hugely expanded the knowledge of plant medicine and ignited a renewed interest in botany, natural history, and gardening throughout the Renaissance period. In fact, during Rembert Dodoens’ lifetime, his extensively illustrated “herb book” became one of the most translated volumes in the world, second only to the Bible.

The Bible itself mentions hundreds of medicinal plants, as well as numerous distilled botanical oils known to have healing qualities, although specific formulations were rarely put into detail, perhaps to avoid spreading knowledge of what early Christians considered pagan or magickal practices. However, throughout her lifetime, the mystic, musician and Benedictine Abbess Hildegard of Bingen managed to find time away from her Biblical studies to contribute a vast amount of scholarly work on plants and their medicinal qualities. She famously wrote,

“Gaze at the beauty of earth’s greenings. Now, think. What delight God gives to humankind with all these things. All nature is at the disposal of humankind. We are to work with it. For without, we cannot survive.”

Bingen’s nine volume series Physica, as well as in her the book Causae et Curae (Holistic Healing), both written between 1150 and 1160, documented not only her own studies of botany, but also the experiences of other (primarily female) healers, many illiterate, whose vast, generational knowledge may have otherwise been lost to time.

In China of the late 1500s, the naturalist, herbalist, and physician Li Shizhen, spent 27 years compiling his Compendium of Materia Medica, which lists hundreds of plants and herbs key to Chinese Medicine modalities.

In 16th century Mexico, what is now known as the Badianus Manuscript was first penned, a detailed overview of ancient Aztec plant medicines, written by the physician, Martinus de la Cruz, and translated into Latin by Juannes Badianus. Both authors were of Aztec descent and students at the College of Santa Cruz in Tlalatilulco, which the Spanish had built soon after colonizing the country. The manuscript is evidence of the incredibly advanced knowledge and sophisticated plant and herbal healing treatments practiced in Aztec cultures.

Throughout the long history of plants and healing there are specific botanicals which have been celebrated again and again as particularly potent curatives. In much of Asia, for instance, Ginger has long been used for its antibacterial and antiviral qualities, as well as to enhance digestion and the absorption of nutrients into the body. Ginseng is another plant used for centuries in Chinese Medicine as a powerful anti-inflammatory. Turmeric has been used across cultures for 4000 years or more and is a core foundational plant in Ayurveda – the holistic, whole body healing practice first founded in India over 3000 years ago. In tropical climates, the Coconut has long offered a host of both medicinal and nutritive qualities. Lavender, native to the Mediterranean, Middle East, and India, was first brought to Europe by the Romans nearly 2000 years ago, and still prized not only for its fragrance, but for its potent healing qualities as well.

In North America, indigenous cultures have long used plants like Yucca, Thistle and Echinacea for curing a variety of illnesses. In his 2020 book, Iwígara: American Indian Ethnobotanical Traditions and Science, indigenous scholar, and ethnobotanist Enrique Salmón documents the extensive knowledge of plant medicine shared by tribal elders and passed on from one generation to the next. “Europeans reached the shores of North America only 400 years ago...” he writes, “...native peoples have been studying, observing, and using the plants of North America for at least 20,000 years.” Salmón goes on to cite over 200 examples culled from this vast Native American pharmacopeia, a range of botanicals prized by indigenous tribes for medicinal use; including plants such as Slippery Elm and a root known as Osha, which Salmón, explains as, “one of the most widely known and used plant remedies.” Sometimes called Bear Root or Indian Parsley, Osha is used for coughs, digestive ailments, and for alleviating headaches and fevers.

In addition to indigenous remedies, much of the plant medicine of the last four hundred years in America, integrate the many cultures arriving to the continent, including an array of traditional healing modalities brought to the United States from Africa. In Michelle E. Lee’s 2014 book, Working the Roots, the author documents several centuries of both African American and Native American plant medicines. In her introduction, Lee explains her thesis for the project was to represent, “a small portion of the medical expertise that enslaved Africans brought from their home- land and blended with the knowledge of the healing arts they found already present among the indigenous people of America.” Lee’s volume documents plant-based teas, tinctures, poultices, and various herbal remedies that were used for both preventive care and serious ailments. Pine tree sap, for example, was utilized to boost immunity. Okra was a staple food on most supper tables for centuries but was also used for its laxative qualities. Elderberry was steeped in boiling water to suppress coughs and soothe sore throats. Most of Lee’s research was conducted through interviews with elders in the African and Native American communities, Working the Roots shows how folk remedies, most consisting of botanical ingredients found within close geographical proximity, have helped nurture the health and well-being of generations.

As we move into the new millenium, there has been a groundswell of interest in plant medicines and holistic healing.

Young botanists, foragers and herbalists are returning with enthusiasm to the traditions of their ancestors, seeking methods of not only healing the body, but also the mind. In his 2010 article “Why Plants Are (Usually) Better Than Drugs,” the pioneering physician Dr. Andrew Weil, explains one of the core tenets of integrative medicine, a practice which encourages not only conventional medical remedies, but the integration of plant medicines as well. “Human beings and plants have co-evolved for millions of years,” he writes, “so it makes perfect sense that our complex bodies would be adapted to absorb needed, beneficial compounds from complex plants and ignore the rest.” That co-existence, thousands of years of symbiotic evolution, has resulted in a bountiful botanical pharmacopeia, a vast apothecary in our forests, our fields, and kitchen gardens. According to Rosemary Gladstar, considered one of the founding voices of the modern herbalism movement, the use of botanicals for healing goes far beyond physical ailments. Gladstar, who has written books on plant medicine and who lectures all over the globe, speaks on the curative powers of plants, professing that the botanical world offers remedies capable of restoring our health, and our emotional, mental, and spiritual well- being.

“The plants,” she claims, “have enough spirit to transform our limited vision.”

PLANT MAGICK

PLANT MAGICK

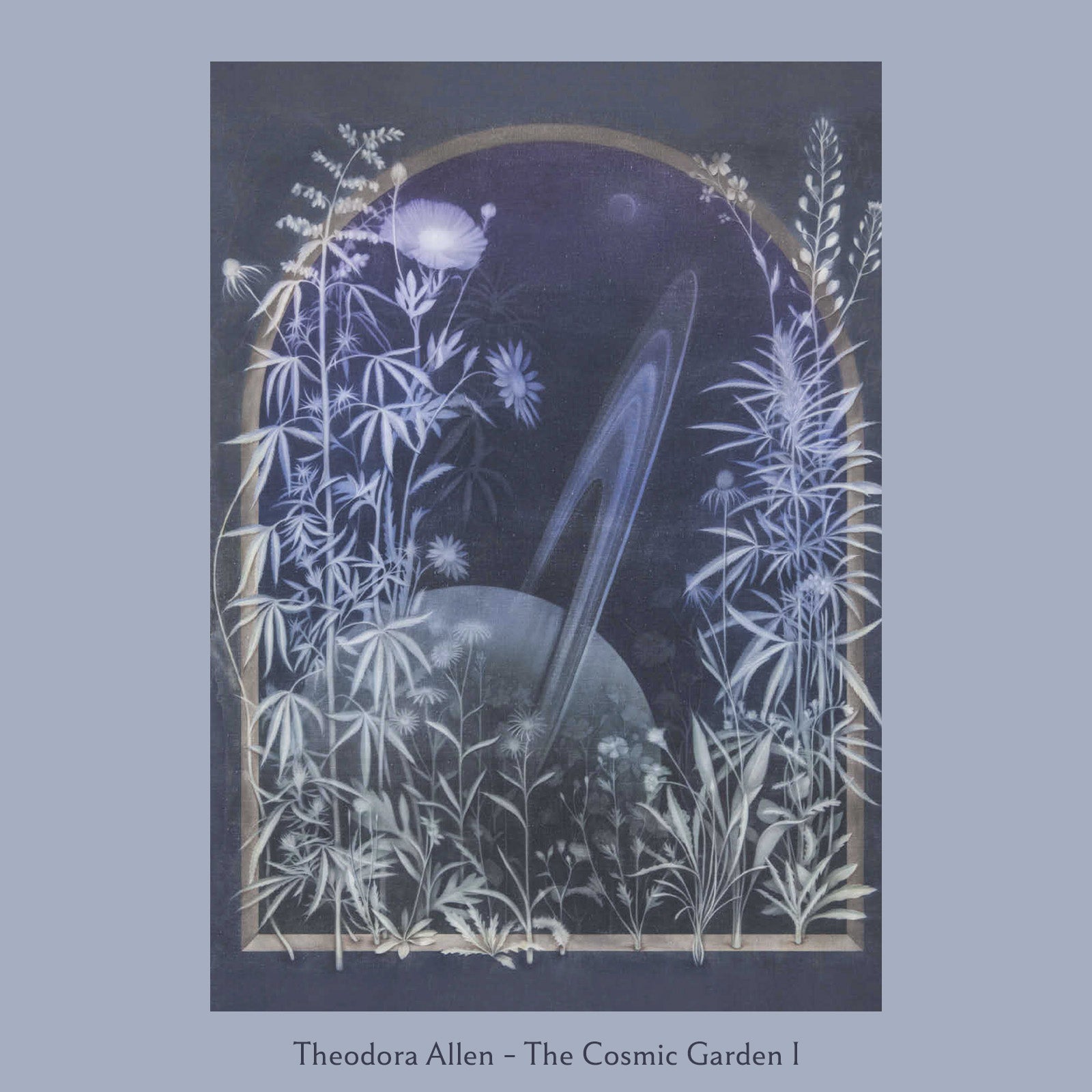

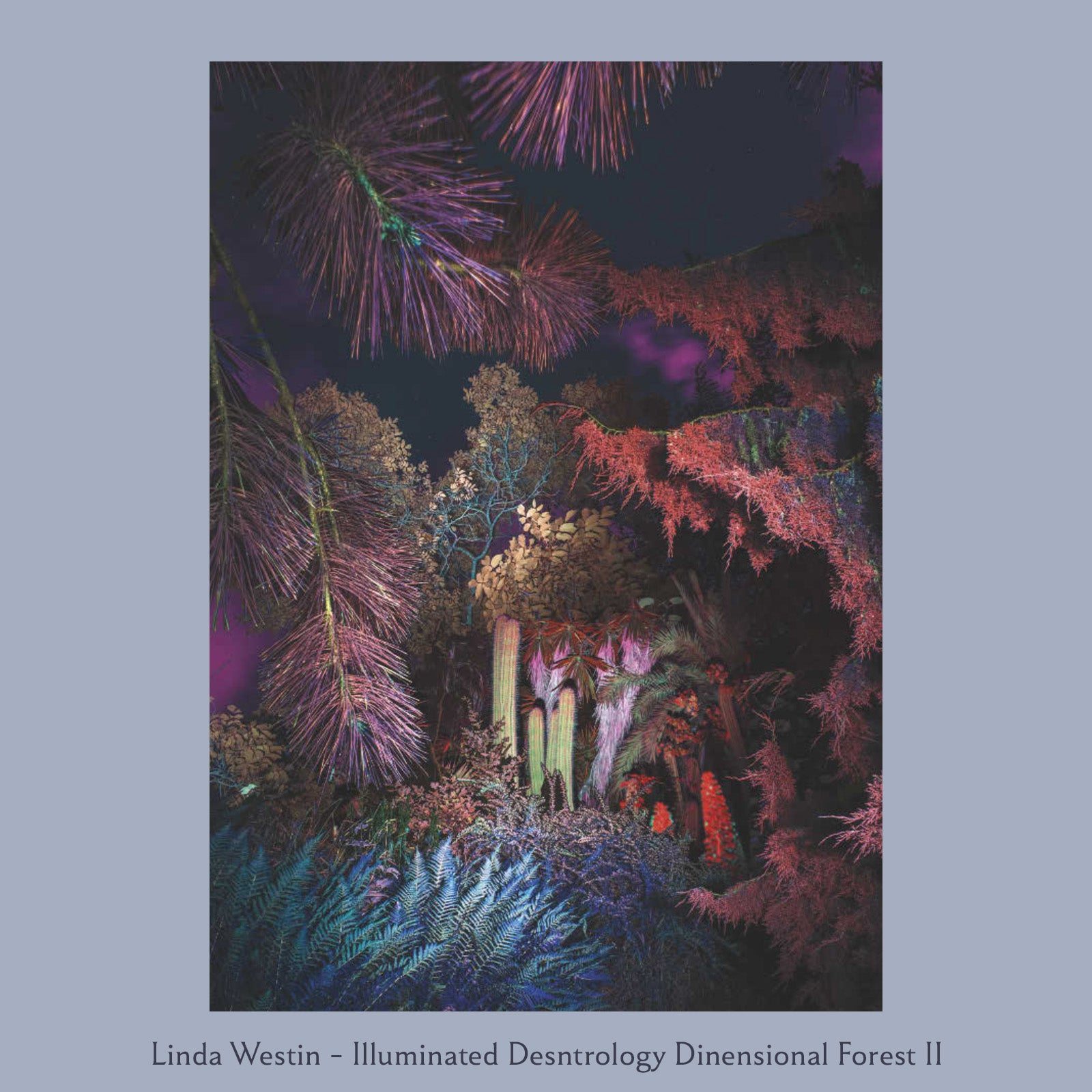

Throughout the ages, metaphysical traditions have been translated into sacred and visionary art. The Library of Esoterica explores the symbolic language of our most potent universal stories.

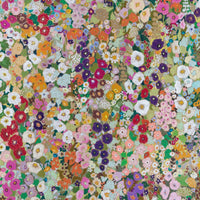

The fourth volume in The Library of Esoterica explores the historic roots of plants in myth and magickal practices. Through essays, interviews, and more than 400 images—from ancient Egyptian stonework to Victorian botanical art, to contemporary works celebrating nature —

Plant Magick chronicles the symbiotic relationship between plants and people.

Add a little magick to your life.