House of Hackney has come together with The Library of Esoterica to bring you a season of Plant Magick through spellbinding essays, events, art and interiors, with the plant as muse.

From root to vibrant blossom, Taschen’s Plant Magick explores the fertile, interconnected history between plants and people. This creative partnership is rooted in a shared reverence for the enchanted, the unseen, and the profound beauty that surrounds us.

When you take a flower in your hand and really look at it, it’s your world for the moment. I want to give that world to someone else. Most people in the city rush around so they have no time to look at a flower. I want them to see it whether they want to or not.

– Georgia O'Keeffe, from an interview with The NewYork Post, 1946

-

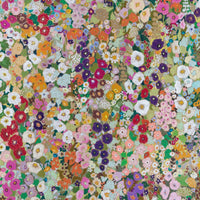

Plants and nature have been the artists’ muse since the earliest cave paintings depicting mushrooms, cactus, and flowers – powdered mineral pigments rubbed onto stone in the flicker of firelight. Nature is inspiration across all mediums and art forms, word to page, ink to canvas, the snap of the shutter. There are certain artists for whom nature was a central and continually evolving motivation to manifest work, artists we immediately align with imagery of flowers or plants, trees, or gardens.

Van Gogh’s sunflowers, vivid and bright, the artist documenting the natural realm with a vibratory, slightly hallucinogenic immediacy. There is Monet in his garden at Giverny, growing wildflowers beside Roses, crawling vines amid tidy shrubs, a garden painted more than planted, organized with the beautiful cacophony of an artist’s palette. There is the Symbolist Paul Gauguin, immersed in his sunlight and Palms, French Polynesian reveries; and the luminous floral explorations of Henri Matisse, once quoted as saying, “There are always flowers for those who want to see them.” Centuries prior, in the 1500s, the Italian painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo created playful detailed paintings by anthropomorphizing plants, fruits and flowers into figures in a series of works that set the natural realm at their center.

Later, the Surrealist Movement would approach nature with the same whimsical eye, playing with size and form, mutating the physical world into multiple dimensions of their own. In Salvador Dalí’s visions, a rose hovers immense and sensual over vast plains of dry grass. In Dorothea Tanning’s dreamlike imagery, a giant sunflower sprawls down a wide staircase, its green stem wrapped seductively around a young woman’s waist.

In the early 20th century, the newly invented medium of photography focused the artist’s lens on natural subjects. The renowned Ansel Adams approached his photographic docu- mentation of trees with a singular intensity, his images capturing and amplifying their innate majesty and power. His contemporary, Imogen Cunningham photographed botani- cals with a gentle, seductive intimacy – a Calla Lily with its feminine curve of white blossom, an agave leaf, large and leathery, its edges intensely serrated. EdwardWeston captured the skin of the common green pepper in lush black and white, the image reminiscent of the smooth, curved back of a woman. Later, the artist Robert Mapplethorpe would bring a similar element of arousal and carnality to his images of plants and flowers, documenting the eroticism of the botanical world with the eye of a lover in longing. Decades earlier, the artist Georgia O’Keeffe would famously state,

“My painting is what I have to give back to the world for what the world gives to me.”

For O’Keeffe, that reciprocal generosity came in the form of lush, fearlessly vivid reflections of the natural world around her, the bleached bones and smooth totemic stones of the New Mexican desert, and flowers – Datura blos- som, crimson Poppies, fringe-petaled Iris – all rendered into sensuous, voluptuous imagery, the viewer pulled in close – seduced.

Artwork: Inka Essenhigh · Rave Scene, United States, 2022

Later Andy Warhol would make nature “Pop,” particularly with his 1964 Flowers, a series of vibrant floral lithographs. Meanwhile, plants were becoming not only a muse to artists, but visionary medicine as well, with the advent of the Psychedelic Art movement and the creation of artwork under the influence of cannabis, magic mushrooms, peyote cactus and other psychoactive plant compounds. The subsequent effects can be seen across the counterculture works of the era, in popular movies and music and on the gallery walls as well, such as in “Looking for Mushrooms,” the 1967 experimental film by the multimedia artist and filmmaker Bruce Conner, and in the groundbreaking works of Marjorie Cameron, specifically her unabashedly feral and sexualized 1961 illustration titled, “PeyoteVision.” The composer John Cage is another example, finding creative inspiration in his mycological studies. The natural world itself would eventually transform into both canvas and medium – most notably in the prolific land art works of Andy Goldsworthy, and in the riotous, oversized, flower-covered sculptures of Jeff Koons, whose 1992 work “Puppy” features a 43-foot-tall depiction of a West Highland Terrier covered by over 60,000 flowering plants. More recently the Japanese artist Azume Makoto has sent floral arrangements into space, set them aflame and encased them in enormous blocks of ice.

The incorporation of natural elements into immersive installations, photographs and other mediums has also become a means of activism, serving to elevate and promote plat- forms for environmental and ecological causes. The South American photographer Sebastião Salgado has continually turned his lens on the vast destruction of the Amazonian rainforest in a quest to raise awareness of climate change and deforestation. His non-profit, Instituto Terra, established in 1998 by Salgado and his partner Lélia, has subsequently planted more than 2.5 million trees in their homeland of Brazil.

Another example is the multi-media artist Yoko Ono’s creation of the ongoing interactive installation, “Wish Tree” which encourages participants to pen their wishes onto strips of paper which are then hung onto living trees. Describing the core intention of the work, Ono explains, “the hope is that these wishes go out to all corners of the planet and give encouragement, inspiration, and a sense of solidarity in a world now filled with fear and confusion. Let us come together to realize a peaceful world.”

Artwork: Marlene Steyn - The flower child with hay fever, South Africa, 2022

PLANT MAGICK

PLANT MAGICK

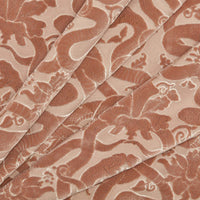

Throughout the ages, metaphysical traditions have been translated into sacred and visionary art. The Library of Esoterica explores the symbolic language of our most potent universal stories.

The fourth volume in The Library of Esoterica explores the historic roots of plants in myth and magickal practices. Through essays, interviews, and more than 400 images—from ancient Egyptian stonework to Victorian botanical art, to contemporary works celebrating nature —

Plant Magick chronicles the symbiotic relationship between plants and people.

Add a little magick to your life.